We are very happy that you like sharing articles from the site. To send more articles to your friends please copy and paste the page address into a separate email.Thank You.

Printer-Friendly Version | Email Article

I hope all of you had an opportunity for some relaxation and re-charging during the summer months.

I’ve often devoted my September article to a school-related theme to coincide with the beginning of the new school year. This month’s column examines the ways in which teachers, parents, youth coaches, and other caregivers understand and respond to the seeming lack of motivation displayed by some children and adolescents. While its content most often focuses on students and the school environment, it has equal relevance for our home environments and other age groups and settings as well. A little background information is warranted.

In my clinical practice and presentations, I have had the opportunity to interview children and adults diagnosed with LD (learning differences/disabilities) and/or ADHD (attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder). I have asked what they found most helpful when dealing with the challenges they faced and what they found least helpful. Most helpful typically involved the presence of supportive adults or what the late psychologist Julius Segal labeled “charismatic adults,” defined as adults from whom children and adolescents “gathered strength.”

A frequent answer to what has been least helpful centered around remarks expressed by adults that were perceived as accusatory or judgmental. One common example is captured in the following response: “I really disliked and became angry when someone told me to ‘try harder.’” As one young adult noted, “How did they know I wasn’t trying hard enough?” He wondered somewhat facetiously, “Is there a test for trying or effort, Dr. Brooks? I often felt I was working twice as hard as other students but without the same positive results.” When I inquired whether he thought comments such as “try harder” or “you could succeed if you just put in more effort” or “you have to learn to show more grit” might, at times, be meant to encourage another person, he answered without hesitation, “No! You don’t encourage kids by judging them and that’s what you’re doing when you say ‘try harder.’”

He continued, “How would teachers feel if they were having difficulty understanding or meeting one of their responsibilities and a supervisor said, “You just have to try harder to be a good teacher?” And, with a touch of humor, he guessed, “I bet they wouldn’t thank the person for using these words.” I agreed with his assessment.

The Consequences of Our Messages

Reflections about these kinds of conversations surfaced when I read an article, “When Parents Tell Kids to ‘Work Hard,’ Do They Send the Wrong Message?” It was authored by Michael Blanding and posted on Harvard Business School’s Working Knowledge. Blanding interviewed Ashley Whillans, a faculty member at Harvard Business School, about the findings of three studies she conducted with Antonya Gonzalez, a psychology professor at Western Washington University, and Lucia Macchia, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School of Public Policy.

Their studies indicate that viewing effort as a cornerstone of success can actually contribute to a misperception of why some people do not succeed in different areas of their lives. Whillans observes, “If you are learning that effort is the way to achieve success, and you see people who have less, you might assume they don’t work hard enough—as opposed to recognizing the systems and institutions we know can stand in the way.” Whillans and her colleagues emphasize that their research is “particularly relevant given that many educators today focus on willpower, grit, and a ‘growth mindset,’ teaching kids that intelligence can be grown like a muscle, and that it’s not inherited or predetermined.”

I found the following comment especially compelling: “There is such an emphasis now with kids on effort and taking control of your own learning and abilities. But it’s not possible for everyone to overcome certain challenges.”

I have long advocated that intrinsic motivation will be reinforced when students feel adults care about them and when they are provided with choices to make about their own education. These conditions are vital components of intrinsic motivation and described in Self-Determination Theory (SDT) proposed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan.

Limiting “Uncontrollable Factors”

The research findings reported by Whillans and her colleagues capture another concept I have highlighted in my work, namely, “personal control.” Her studies demonstrate that those parents who attribute success to effort are likely to pass that view to their children. Whillans asserts that the problem is that “children who believe that inequality is due to lack of effort are less likely to rectify that inequality.” Why attempt to rectify a situation that is perceived, as one of my patients described, as “a personality flaw of laziness” in the person who is not successful?

Whillans adds, “We want our children to believe that they can work hard and get ahead as a function of their effort but, unfortunately, the world doesn’t work that way. People are struggling to make ends meet around the country, and success is often determined in part by uncontrollable factors that are complicated to talk with their kids about.”

As many of my readers are aware, I have long suggested that adopting an attitude of “personal control” and focusing our time and energy on situations over which we have some influence rather than on situations over which we have little, if any, control, is an essential component of resilience. However, when “uncontrollable factors” greatly limit personal control, it is incumbent upon adults in the child’s life to address and weaken these factors to ensure that a child’s “controllable behavior” will lead to a successful outcome.

A position similar to that taken by Whillans and her colleagues was advanced in a Working Paper issued by the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child at Harvard University, titled, “Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience.” This report contends, “When overcoming the odds is erroneously viewed as simply a matter of individual motivation or grit, the failure to succeed is perceived as the fault of the individual and ‘blaming the victim’ becomes the most frequent response.”

Educator Linda Nathan echoed this view in her book When Grit Isn’t Enough, concluding, “Grit puts the focus on student initiative, often ignoring social and economic factors that can undermine even the best of efforts.”

The research of Whillans and her colleagues and the stance assumed by Nathan and the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child focus primarily on social-economic inequities that represent major obstacles for children to be successful in important domains of their lives. Given what I have learned working with many children and adults with LD and ADHD, struggles with learning and executive functioning also represent significant barriers to achieving goals, barriers that result in behaviors often interpreted as a lack of effort or motivation by others in the child or adult’s life.

To Reinforce Hope and Dignity

A key challenge for teachers, parents, and other caregivers, especially those raising or teaching children who face noteworthy struggles, is to adopt a mindset in which these struggles are not perceived as a consequence of laziness or not trying hard enough but rather as barriers that restrict a child’s possibility for success. The following are features of a mindset that I believe will prompt adults to respond in ways that strengthen a child’s hope and dignity:

To believe that every child from birth wants to succeed. When I was in graduate school, well before my adoption of a strength-based approach and the emergence of the field of positive psychology, I became intrigued by the writings of Harvard faculty member and psychologist Robert White. The latter proposed that from birth there is a need in all children to master their environment. It was seen as a need for efficacy, a need that is witnessed on a daily basis by the persistence of infants and toddlers to walk after falling countless times, to finish building a tower of blocks following multiple collapses, to continue to learn new skills each day. In my most recent book, Tenacity in Children: Nurturing the Seven Instincts for Lifetime Success, co-authored with my colleague Sam Goldstein, we offer support for the presence from birth of a drive for effectiveness and intrinsic motivation.

To appreciate the impact and presence of “avoidance motivation.” As I began to cite the work of White and the inborn nature of intrinsic motivation, I was often greeted with an important question, “If children are born with a drive for efficacy and a need to master the challenges they face, why is it that so many children fail to meet their responsibilities, or quit at different tasks, or fail to do their work in school?” One teacher became even more specific by asking, “Dr. Brooks, you were principal of a school in a psychiatric hospital. Did any of your students ever refuse to do their work or disrupt the class or even fall asleep during class?”

My answer, of course, was “yes,” which prompted a follow-up comment, “Well, those kids didn’t seem very motivated to learn, so what happened to this inborn drive for effectiveness? They weren’t even trying to succeed at your school.” These were important observations, prompting a consideration of what forces derail a drive for efficacy.

In fact, these students at this school in a psychiatric hospital and many students at countless other schools are indeed motivated even when not engaging in school tasks. As others have observed, including my colleague Rick Lavoie, a very strong form of motivation in students, especially those facing significant learning and behavioral struggles, is “avoidance motivation.” These students, rather than displaying motivation to confront a task, expend much of their time and energy to avoid the task.

A child or adolescent’s use of “avoidance motivation” invites the question, “Why is it that for some individuals the need to avoid a challenge has become more dominant than the desire to engage in meeting that challenge?” I believe there are different reasons for this situation. A couple of noteworthy factors involve the wish to avoid those situations that we believe are likely to result in ongoing failure and humiliation or that tax us physically and emotionally without any promise of success. I vividly recall a 10-year-old boy I saw in therapy with a diagnosis of LD and ADHD. He would often push or hit classmates for no apparent reason. As he came to trust me, he offered the following insightful explanation of his behavior: “I would rather hit another kid and be sent to the principal’s office than have to be in the classroom where I felt like a dummy and was always told to try harder.”

To understand and lessen “avoidance motivation.” How might our actions change if we are open to accepting that certain behaviors displayed by children and adolescents (and adults) are not rooted in laziness or a lack of trying but rather represent an often desperate attempt to avoid failure, humiliation, and emotional exhaustion in what is perceived to be a less than supportive environment? I believe that such an acceptance will allow us to be in a more favorable position to assume the role of a charismatic adult. We will be more receptive to support rather than criticize youngsters who are already burdened by an uneven playing field—a field dotted with socio-economic, racial, and learning disadvantages. It will encourage us to ask, “What is it that I can do to lessen avoidance motivation in a child (student) who uses it as a way of coping?” or “What is it I can do to lessen the disadvantages these children face on a regular basis so that they will be less likely to resort to avoidance motivation?”

I am aware that answers to these questions represent a wide spectrum of solutions, which could easily fill an entire book. There are certainly large, systemic issues related to racism and poverty that must continually be addressed. Children who come to school hungry, tired, and anxious and then feel judged for not embracing schoolwork are susceptible to displaying avoidance motivation—especially when interacting with adults whom they perceive as lacking in compassion and empathy.

While larger systemic issues cannot and should not be ignored, we must remember that we can apply effective strategies to lessen avoidance motivation by focusing our time and attention on what may be considered a “micro-level.” Seemingly simple actions as having breakfast and lunch provided by caring, nonjudgmental adults at school may make a profound difference in whether students succeed in school or not.

We can learn a great deal interacting with and improving the lives of small groups of students or even individual students. An illustration of a micro-level intervention is based on one of my favorite strategies. I’ve often emphasized that there is research to indicate that the dropout rate among disillusioned, failing high school students is decreased when they are given opportunities to help other students (e.g., reading a couple of hours a week to elementary school students). Engagement in what I refer to as “contributory” or “charitable” activities serves to reinforces positive emotions, resilience, and a sense of purpose in the school setting. These factors not only reduce the need to rely on avoidance motivation, but they also increase intrinsic motivation (I have written about contributory and charitable activities on many occasions. Please see my June, 2022 article as one example).

Viewed from another perspective, Whillans describes the benefits of charitable activities undertaken by children born in more affluent homes to help them gain a greater understanding and be less judgmental of those facing many disadvantages. She observes, “The families that have the most, often also have the most to give, and conversations about why and how to help others are powerful. Our studies show that the way parents explain why some people have more than others in society can fundamentally shift what their kids believe, and maybe even what their kids do to rectify inequality over the course of their lives.”

One more example of a micro-level intervention for confronting avoidance motivation is in evidence when an adult conveys empathy and compassion rather than accusation and judgment towards a struggling student. A simple comment—a microaffirmation—such as “I can see that you’re having some difficulty with this assignment. I think together we can figure out what will help” can have a major positive impact on that student.

Concluding Comment

Many of the observations and suggestions offered in this article are rooted in what I have referred to as “empathic communication.” Such communication invites us to consider the following questions:

“In anything I say to my child (student), what do I hope to accomplish?”

“Would I want anyone to say to me what I have just said to my child (student)?”

“Am I saying or doing things in ways in which my child (student) will be most likely to hear what I have to say, not become defensive, and be willing to cooperate with me?”

I believe we will be in a better position to be a charismatic adult for the children and students in our care if we carefully reflect upon these questions and ask how we might interact with them so that they perceive us as supportive, caring, and encouraging. We will all be the beneficiaries of such a positive climate.

*******

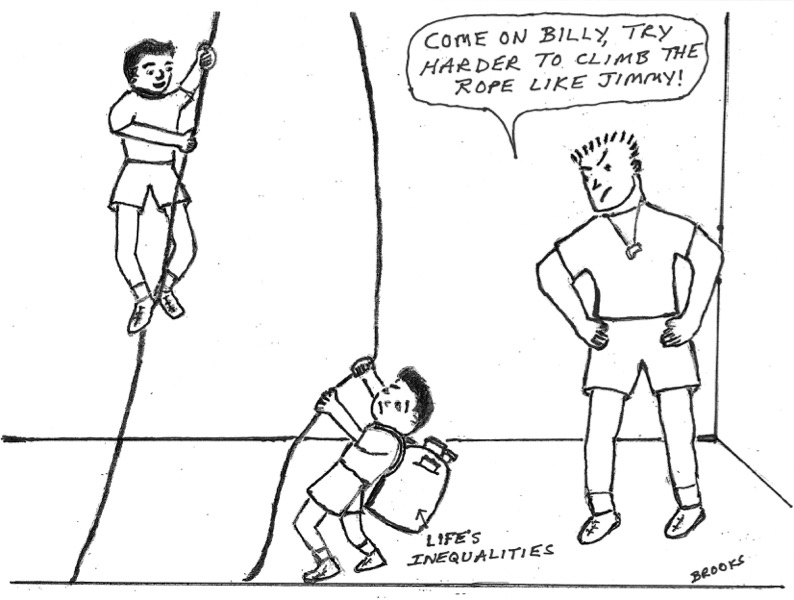

If You Would Like to Know the Back Story to the Cartoon in this Article

At my recent birthday at the end of July, which was celebrated at my son Rich’s house in Scarborough, Maine, my niece Cheryl gave me a sketching pad with colored pencils and pens and a couple of Sharpies. Cheryl wrote a lovely note in her birthday card. She said that a very fond memory of her childhood was when I regularly mailed her cartoons I had drawn. Most represented happenings in her and her family’s life. Once I began college, other interests took me away from cartooning. As a therapist, I drew cartoons from time to time for some of my child patients that captured in imagery key issues with which they were dealing (e.g., perfectionism, separation anxiety, the divorce of parents), but that was the extent of my cartooning.

Cheryl said she hoped I would begin cartooning again and even suggested I draw a cartoon for one of my monthly articles. I said I would consider doing so. A few days after my birthday, while going through some old files, I found an Art Folio from seventh grade when I was a member of the Art Club. It contained three cartoons I had created as well as drawings of two of my favorite subjects at that time of my life: knights and automobiles. I had not seen this Folio in years, but somehow it was discovered just a few days after Cheryl’s gift. The Folio prompted memories of when I drew a cartoon about not littering in school, and I won an award for my effort. My finished product was placed on a wall in a hallway in the school.

One other occurrence pertaining to my drawings. Several years ago I reconnected with two childhood friends, Sandy and Larry, and we now have monthly Zoom calls, which are truly delightful as we chat about our old neighborhood in Brooklyn and memories of friends and teachers. Sandy recalled how much I enjoyed drawing.

Talk about karma! I could not help but conclude that these different events were a call for action for me to return to doing some cartoons. I purchased a book about cartooning. Not surprisingly, I then found that there was a great deal of material about cartooning on the internet, including videos on YouTube (what subject matter is not on YouTube these days?). I must admit that as I begin to draw cartoons again, I found it wasn’t like riding a bike for the first time in years and quickly being able to maintain balance. I thought some of the cartoons I created in seventh grade were more advanced than my current ones.

As this process of “re-learning” the skills associated with cartooning took place, I began to write my September article. Having promised Cheryl I would attempt to draw a cartoon for one of my articles, I thought, “Why not for this article?” However, I soon questioned if it would be wiser to wait several more months before posting a drawing, when hopefully my cartooning proficiency will be more advanced.

My wife Marilyn proofread my September article—as she does for all of my articles—and was very complimentary about its content. Shortly afterwards I finished the cartoon and showed it to her as I voiced hesitancy about including it as the visual attachment for the article. Fortunately, Marilyn didn’t say “try harder” to draw a better cartoon. Instead, she said I should definitely post it, that it very nicely captured the main theme of the article. I remained hesitant, thinking that I need much more time to refine my skills before “exposing” my work to a large audience. Then I reminded myself that as a therapist I often encourage children and adults to take some risks in their quest to reach certain goals. And so, perhaps much sooner than planned, I have included the cartoon.

And thank you, Cheryl, for encouraging me to return to a favorite activity of my childhood and adolescence.