We are very happy that you like sharing articles from the site. To send more articles to your friends please copy and paste the page address into a separate email.Thank You.

Printer-Friendly Version | Email Article

David was 16 years old in early 1921 when he immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe. His father was killed during World War I. He was the oldest son in his family and his goal was to come to America and earn enough money to send for his mother and three siblings. He secured work in a shoe factory. He saved most of his wages, enabling him to fulfill his dream of having his family join him, which they did within three years.

David was 16 years old in early 1921 when he immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe. His father was killed during World War I. He was the oldest son in his family and his goal was to come to America and earn enough money to send for his mother and three siblings. He secured work in a shoe factory. He saved most of his wages, enabling him to fulfill his dream of having his family join him, which they did within three years.

Similar to the story of many immigrants at that time, David left a small town in Europe, the only place he had ever known, to board a ship and travel to a new country thousands of miles away. He made the decision to embark on this journey—a journey filled with many unknowns and uncertainties and without the benefit of family or friends to accompany him—to seek a future that offered hope for a better life. It was fortunate he made the choice not to remain in Europe. While he had experienced anti-Semitism in his town, little could he imagine the extent of the horrors that were to emerge in Europe in the subsequent years, culminating in World War II and the Holocaust. The entire Jewish population of his town was annihilated.

Many years later David’s youngest adult son, Bobby, told his father that he couldn’t imagine at the age of 16 leaving the only place he had ever known to travel alone to a new country so far away. David replied that the conditions were very different from those under which Bobby had grown up. He told his son that the uncertainties he faced coming to America were small compared with the harsh reality of what he was leaving—a Europe still in turmoil after World War I, his father lost in the war, food being scarce, Jewish people facing pogroms.

David shared with Bobby an unforgettable memory from when he first arrived in New York. He was walking on the Lower East Side, a location filled with tenements overflowing with thousands of immigrant families. David recalled with a smile that while the streets of America were not “paved in gold” as had been rumored in some of the small towns of Europe, there was something that immediately caught his attention. He explained that he was in awe of the many small pushcarts on the streets selling different kinds of food. He said he had never seen so much food in his life!

“So Much Food”

In hearing his father’s memory, Bobby thought that the recollection of “so much food” was a symbol to his father that this new country, of which he knew so little, truly offered a promise of a better life, one that he would never realize in his former town in Europe. As his father described his initial impressions of the United States, Bobby could not help thinking of several of the lyrics of Neil Diamond’s song “Coming to America”:

Everywhere around the world

They’re coming to America

Got a dream to take them there

They’re coming to America

Got a dream they’ve come to share

They’re coming to America.

David met his wife, Eva, in New York City. She also emigrated from Eastern Europe, the only child from the marriage of a widow and widower. Eva had many half-siblings (she would cringe if anyone ever used the word “half” to describe them). When she was brought to America by her parents in 1922, her siblings, some of whom were more than 20 years her senior, were already in North America. On her mother’s side most settled in New York City, while on her father’s side, they went to Rochester, New York and eventually a number moved to St. Catharines, Ontario.

Eva and David shared a wonderful, loving marriage and had four sons. For many years David owned a small candy/cigar store. While finances were modest, they lived a secure life, mostly in Brooklyn, where they raised their sons.

David and Eva were my parents. I’m known by many in my family as Bobby. I was their youngest son—earning the title of “youngest” by 70 minutes, which is quite a lengthy time between the birth of twins. My late twin brother Michael, whom I wrote about shortly after he died in my February, 2013 article, “decided” to come into this world first. We had two older brothers, Henry and Irwin, who were approaching 13 and 10 years of age when we were born. Apparently, years after the birth of Irwin my mother “convinced” my father that they should “try” for a girl. And their “try” resulted in twin boys! One more detail: my mother didn’t even know that she was having twins until Michael was born. I guess I was quite a surprise!

Reflections on a Family’s Journey

I often think about my parents and how fortunate I was to grow up in such a loving home. During the past few weeks and months, I’ve been thinking about them even more, especially my father’s experience coming to America by himself. Several events have served as a catalyst for this increased interest. One has been the recent political circumstances that have unfolded in the United States, punctuated by the unforgettable scenes of the storming of the Capitol on January 6 and the messages of calm and hope expressed on the same site two weeks later on Inauguration Day.

A second has been that two very dear cousins of mine in Toronto, Carol and Todd Herzog, sent me an album containing photos of my parents, especially of my mother with family and friends, taken from the mid-1920s through the early 1950s. Carol and Todd told me that they were doing some decluttering in their house and found these photos that they thought would be of interest to me. They were.

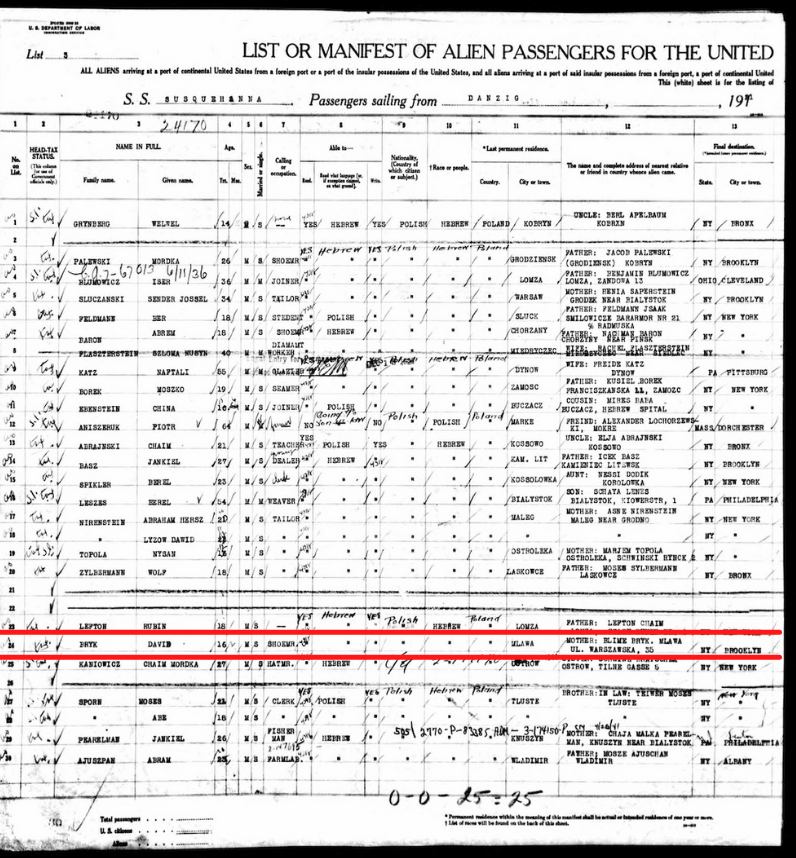

And third, my daughter-in-law Suzanne, while researching her parents’ family history, has also traced my parents’ roots. Given Suzanne’s persistence and excellent investigative skills, I now possess papers that document when my parents arrived in the United States, when they were married in St. Catharines, when my mother’s parents died (both in Rochester), the towns in which my parents were born, and the passenger manifest of the ship my father boarded on his way to America.

Not surprisingly, the documents and photos elicited many thoughts and emotions. What a warm feeling I experienced as I looked at photos of my mom and her friends in their late teens and early 20s, posing playfully for the camera. How joyous they appeared in their 1920s garb. There were scenes on a beach, at a farm in which my mom was dressed in overalls holding a shovel (not certain what that was about), another in which she was throwing snowballs, one in which she was playing a ukulele, a number in which she was very fashionably dressed, and quite a few with different young men—many of these photos were taken when she was 18 years old, prior to meeting my dad. She seemed to have a busy social life! And there were lovely photos of my parents together and later with their sons.

Of all of the documents and photos I reviewed, I think I was most moved by the “manifest of alien passengers” of the ship that brought my father to America. He was listed as David Bryk, a last name changed to Brooks when he arrived in the United States. I attempted to imagine him as a 16-year-old as he boarded that ship. What was he thinking? What were his experiences crossing the Atlantic Ocean? What conversations did he have with others on the voyage? I know from our previous discussions that his hope of what America promised overshadowed the uncertainties and anxieties of leaving Europe. I wish I had asked him more about that journey on the ship.

The Word “Uncertain”

Since the emergence of the coronavirus last March, I have frequently used words such as unprecedented, uncertain, disruptive in my writings and webinars to describe these challenging times. As I was writing this column, I realized that the word uncertain appeared several times in my attempt to capture what my father faced as he sought a better life by coming to America. I find “uncertainty” to be an intriguing concept, so much so that in next month’s article I plan to examine the ways in which it ties to one of my favorite concepts: resilience. In the remainder of this article, I want to share a few reflections about recent events in the United States and the ways in which they prompted thoughts about my father’s early experiences coming to and residing in this country.

Much has been written about what transpired on January 6 and, as some have suggested, it may take its place among other historical dates in which the United States was attacked, including September 11 and December 7. The vast majority of Americans, regardless of their political affiliations, were appalled by the storming of the Capitol. As more videos of the insurrection emerged, the extent of the vandalism and desecration of the Capitol Building became increasingly apparent. The physical destruction was very disturbing to view, but as disturbing if not more so was the murder of a Capitol police officer, and the injuries incurred by many other officers. The frenzy of the mob, the shouts to hang Vice President Mike Pence for his failure to overturn an election that he didn’t even have the authority to overturn, the rioters searching for Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and invading her office, and Congressional staff barricading themselves in rooms fearful of being assaulted, were situations that will not or should not be easily forgotten. As we already knew and as we witnessed on January 6, words are very powerful. On that morning, words used by a president and several others, including his personal lawyer, certainly appeared to provide the fuel that resulted in an insurrection.

Not only were most Americans deeply horrified by what occurred at the Capitol, but this horror was shared by people from throughout the world. It is at such times that one appreciates how vulnerable a democracy can be and how steadfastly and diligently we must protect it. From the comments I read offered by world leaders, especially those who consider themselves our allies, America is perceived as the model of democracy, as a beacon of light shining against injustice and tyranny, as a land of hope. This positive image of America as a bulwark of freedom, compassion, and opportunity goes back many years as was reflected, for instance, in poet Emma Lazarus’ famous words written in 1883, etched in bronze and mounted on the pedestal of the Statute of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

I wondered what my parents would have thought of the destructive actions occurring on January 6. Certainly, during their lives they experienced many disturbing, unsettling, disruptive events. As obvious examples, both were in Europe at the time of World War I and the pandemic of 1918, and both were in America during the Great Depression and World War II. While my parents had many happy, satisfying times, they also endured the very painful death of my brother Irwin, an Air Force officer, in 1958, after terrorists placed a bomb on his plane, killing him and his crew.

I believe that similar to what I think my father focused on when he boarded a ship to America, my parents would not minimize the horrors that transpired on January 6 but instead would recommend that we reflect upon the Inauguration ceremony on January 20, a ceremony that vividly demonstrated that the insurrection that took place only two weeks earlier on the same site could not halt the peaceful transition of power—even if this process required the presence of thousands and thousands of members of the National Guard and police officers. At that ceremony, instead of the vitriolic hatred and divisiveness spewed on January 6, we heard messages extolling the importance of hope and calm, of empathy and understanding, and as President Biden emphasized a number of times, a need for “unity.”

A Heartfelt, Memorable Poem

In ending, I wish to cite the poignant, powerful, beautifully written and delivered words of Amanda Gorman, the first National Youth Poet Laureate. She recited her poem “The Hill We Climb,” during the Inauguration. Her poem captured for me what I believe were some of the dreams and hopes my father possessed as a 16-year-old boarding the ship to America. What follows are two brief passages from her memorable poem:

Now we assert

How could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?

We will not march back to what was

but move to what shall be

A country that is bruised but whole,

benevolent but bold,

fierce and free.

Ms. Gorman ended her poem with the following words:

The new dawn blooms as we free it

For there is always light,

if only we’re brave enough to see it

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

In considering these words, I feel a great deal of gratitude that 100 years ago my father—followed two years later by my mother–and I might add so many other immigrants, were brave enough to embrace uncertainty and seek and follow a light of hope.