We are very happy that you like sharing articles from the site. To send more articles to your friends please copy and paste the page address into a separate email.Thank You.

Printer-Friendly Version | Email Article

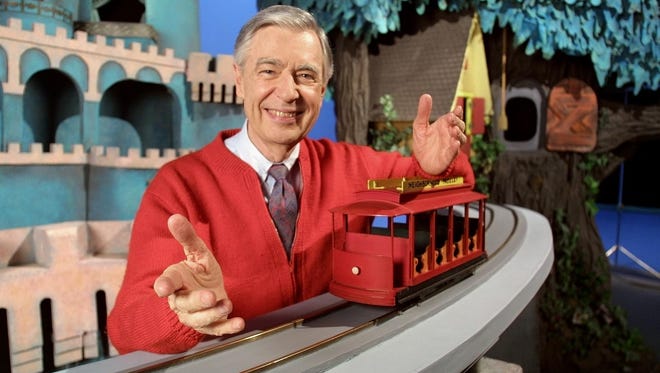

In 2018 my wife Marilyn and I saw the documentary “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” that focused on the life of Fred Rogers, more commonly known as “Mister Rogers.” His television show “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” aired nationally for more than 30 years and was watched by millions of children and their parents. And as the years went by, the children of these children became regular viewers. From one generation to the next, his obvious respect for and love of children never wavered.

In 2018 my wife Marilyn and I saw the documentary “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” that focused on the life of Fred Rogers, more commonly known as “Mister Rogers.” His television show “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” aired nationally for more than 30 years and was watched by millions of children and their parents. And as the years went by, the children of these children became regular viewers. From one generation to the next, his obvious respect for and love of children never wavered.

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” examined both Mister Rogers’ personal and professional lives. Interviews with those associated with the production of his television show together with observations offered by his wife and two sons allowed us to learn more about a man who drew upon his own childhood experiences to address such important topics as compassion for oneself and others, death, divorce, racism, and terrorism. He never spoke down to his young audience when dealing with these themes. His words were rooted in empathy, in an exquisite understanding of the world of children, of their thoughts and feelings.

Mister Rogers proved that one could be direct and forthright in discussing challenging subjects with children and yet comforting at the same time. His kind face, his carefully chosen words, his soft voice all conveyed a sense of reassurance, a feeling that while problems existed in the world, there were many good people who could help children feel secure. In observing Mister Rogers’ actions from a resilience lens, I felt he was transmitting a message I often herald in my presentations and writings, namely, resilient children and adults see problems as things to be solved rather than overwhelmed by. His was a message of reason and hope.

In the showing of the documentary that Marilyn and I attended something occurred at its conclusion that is rarely experienced in a movie theater. The audience, comprised of individuals of all ages, spontaneously applauded. Such a response is typical at the conclusion of a live play, but I can’t remember the last time I was at a movie that elicited applause. I think the reaction spoke to how moved the audience was by the values of empathy, kindness, and decency so vividly captured by Mister Rogers—qualities that are often lacking in the divisive world in which we live.

“What Would Mister Rogers Do?”

During this past holiday season Marilyn and I went to see “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood,” a movie in which Mister Rogers is portrayed by Tom Hanks. It is based on a 1998 article written by Tom Junod and published in Esquire with the title “Can You Say . . . Hero?” Junod had been assigned to interview Rogers for a special issue that centered on American heroes. The editor requested a 400-word article but, given the relationship that transpired between Junod and Mister Rogers, the final product was considerably longer.

Junod recently wrote a piece for the Atlantic titled “What Would Mister Rogers Do?” He noted that given some creative liberties taken in the movie, especially in terms of scenes involving his father, he preferred that his real name not be used. Instead, in the movie he is known as Lloyd Vogel. Junod observed that even with this change of name the movie accurately captured the authenticity of the friendship he developed with Mister Rogers and the impact of that friendship on his life.

In the Atlantic article Junod recalled, “A long time ago, a man of resourceful and relentless kindness saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself. He trusted me when I thought I was untrustworthy, and took an interest in me that went beyond my initial interest in him. He was the first person I ever wrote about who became my friend, and our friendship endured until he died (in 2003).”

Junod recounted that he is frequently asked what Mister Rogers would make of the intense divisiveness and polarization that currently exist in our country and world, of the increase of mass shootings, of the anger and hatred spewed with regularity and impunity on social media towards particular individuals or different ethnic and religious groups—anger that is often translated into acts of violence.

In reflecting upon his interactions with Mister Rogers, Junod was certain that if Mr. Rogers were alive now, his prominent response to today’s events would be predicated on a principle that guided his work, asking us to remember, “You were a child once too.” Junod asserted that Mister Rogers would express this message to “doctors, politicians, CEOs, celebrities, educators, writers, students, everyone. He wanted us to remember what it was like to be a child. . . . He would continue to urge us, in what has become one of his most oft quoted lines, to ‘look for the helpers.’”

“Look for the helpers” resonated with me. It reminded me of a basic finding in the resilience literature, namely, how in order to be resilient we require what the late psychologist Julius Segal called a “charismatic adult” in our lives, an adult from “whom we gather strength.” Such adults provide the support and connections we need to feel less lonely and more connected with others, to be more hopeful and resourceful in the face of adversity and turbulent times.

The encouragement of Mister Rogers to “remember what it was like to be a child” touches directly on a theme I have highlighted in my presentations and writings, the importance of being empathic, in seeing the world through the eyes of children or, as he proposes, through the eyes of ourselves when we were children.

I believe that the continued attraction of Mister Rogers almost 17 years after his death and the popularity of both the documentary and the Tom Hanks’ movie provide testimony to the ways in which his messages and outlook are so relevant and welcome during these stress-filled times. For anyone who might question whether or not there is an increased level of stress, a recent survey sponsored by the American Psychological Association and conducted by the Harris Poll confirmed what many of us recognize in our daily lives. The survey found that compared with a similar study in 2016, the level of stress of Americans has risen, especially about such events as the next presidential election, mass shootings, the cost of health care, and racial and ethnic harassment and discrimination.

Lessons from Mister Rogers to Help Us Be True Neighbors

What messages can we take from the work of Mister Rogers as we “look for the helpers”? Shea Tuttle, author of Exactly as You Are: The Life and Faith of Mister Rogers, offered her thoughts in an article published by The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California-Berkeley. She wrote, “It seems we sense that Mister Rogers, whom we used to know so well, who used to seem to know us so well, may have something to say to us in our divided, contentious, often-painful cultural and political climate.”

Tuttle identified seven “lessons that could help us weather today’s ups and downs, stand up for what we believe in, and come together across our differences.” The following are a list of those lessons together with my brief commentary:

It’s okay to feel whatever it is that we feel. Both positive and negative emotions are part of each person’s life, not to be denied but rather understood and managed. I have heard both my child and adult patients either criticizing themselves for harboring negative feelings or blaming others for the presence of such feelings. No one wants to be told that their feelings are “wrong” or that there is something wrong with them for having certain feelings.

But our feelings aren’t an excuse for bad behavior. Most parents can recall a time they advised their children, “It’s okay to be angry with your brother/sister but not to show your anger by hitting him/her.” A basic developmental task is to learn how to express our feelings in ways that are not physically or emotionally hurtful to others. Sadly, the rhetoric of many politicians and others in leadership positions does not reflect the civility and kindness advocated by Mister Rogers. We must remember, however, that when civility is threatened in society, we must be active in counteracting this situation by taking responsibility for displaying decency in our interaction with others.

Other people are different from us—and just as complex as we are. Tuttle described the significance of this message by noting that when polarization dominates our world we become more vulnerable to demonizing and oversimplifying those with whom we disagree. Mister Rogers reminded his child and adult viewers that we must be careful not to label people as “all good” or “all bad” since such perceptions make it difficult to be empathic and discover common interests and goals.

It’s our responsibility to care for the most vulnerable. I am reminded of a quote often attributed to Mahatma Gandhi, “The greatness of a nation is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” Tuttle observed that Mister Rogers, who was an ordained Presbyterian minister, “took seriously the scripture mandate to care for the most vulnerable. He worked with prisons to create child-friendly spaces for family visitation, sat on hospital boards to minimize trauma in children’s health care, visited people who were sick or dying, and wrote countless letters to the lonely.” I have long advocated that we engage in what I call “contributory” or “charitable” activities that enrich the lives of others and, as importantly, we provide opportunities for our children to do the same. Lecturing children about the importance of being compassionate is a far less effective teaching tool than modeling such behaviors and finding realistic paths for our children to learn about and demonstrate caring.

We can work to make a difference right where we are. How often have we heard the refrain, “I’m just one person, what difference can I make?” Sadly, some people have offered that view for not casting a vote, but we know that one vote can make a difference as a recent election in Boston demonstrated—thousands of votes were cast and the outcome was determined by one vote. The problems we face may at times seem overwhelming, but it is wise to consider the small steps each of us can initiate within our own community to make a difference.

It’s important to make time to care for ourselves. One of my most requested workshops centers on this lesson. I often title it: “Can We Take Care of Our (Students, Children, Patients) if We Don’t Take Care of Ourselves?” As my readers are aware, many of my website articles during the past several years examine practices related to improving our physical and emotional well-being, including regular exercise, a healthier diet, and meditation. If parents and other caregivers feel depleted, it is difficult to help our children become more resilient.

We are neighbors. Tuttle observed that Mister Rogers intentionally used the word “neighbor,” noting, “When Mister Rogers called us neighbors, when he hosted us in his own Neighborhood for over 30 years, he was calling us—gently but firmly—out of our structures of power and our silos of sameness, into lives of mercy and care for another.”

What a powerful message!

Divisiveness, polarization, and lack of civility are not new phenomena. However, the presence of these negative forces seems more evident and more intense than in past years, promulgated and rapidly spread in great part by what most of us consider to be the misuse of social media.

Let us consider the words of Junod at the conclusion of his Atlantic article. “That he (Mister Rogers) stands at the height of his reputation 16 years after his death shows the persistence of a certain kind of human hunger—the hunger for goodness.”

I believe that one of the best ways to honor Mister Rogers’ legacy and satisfy the hunger for goodness is to reflect and act upon the messages culled from his work by Tuttle.